In Jim Shepard’s short story The World to Come, time is measured in diary entries. Within the recollections of an 1856 farmer’s wife, a familiar quiet passion grows between our narrator, Abigail, and her neighbor, Tallie. Though she writes of sweet embraces, any explicit physical connection between the two women is left in the silences of her pen. In Mona Fastvold’s film adaptation, based on a screenplay by Shepard and Ron Hansen (The Assassination of Jesse James) those silences are filled by captured kisses, charged glances, and stolen moments of surging intimacy played beautifully by Katherine Waterston and Vanessa Kirby.

The title of The World to Come suggests a future, perhaps the future we live in now, where same-sex union is acknowledged and Abigail and Tallie would be able to build a life together as partners or even wives, free from the threat of persecution and jealous husbands. In the final passage of the short story and final frames of the film, Abigail longs for this world, imagining herself contentedly and quietly living out her days with Tallie at her side. But the shattered world of her present only highlights the impossibility of this other, distant world, even farther than the places she marvels at in her atlas.

The problem, however, is that this world was very much already possible. The rural America of 1856 as envisioned by Jim Shepard (in the film, less so in the story) is one built on an assumption many audiences have about the history of queer connection and suffering. It exists in that trope-laden idea of an America where, prior to our most immediate present, gay people were universally punished if not killed for merely existing. This of course did happen and still does, and the stories of those victims serve as vital reminders of the LGBT+ community’s tenuous sense of safety in this world. But progress is never linear, and the legacy of queer people - specifically women, and their ability to exist authentically in society is at once both far more nuanced yet far more simple than this image of our past would imply.

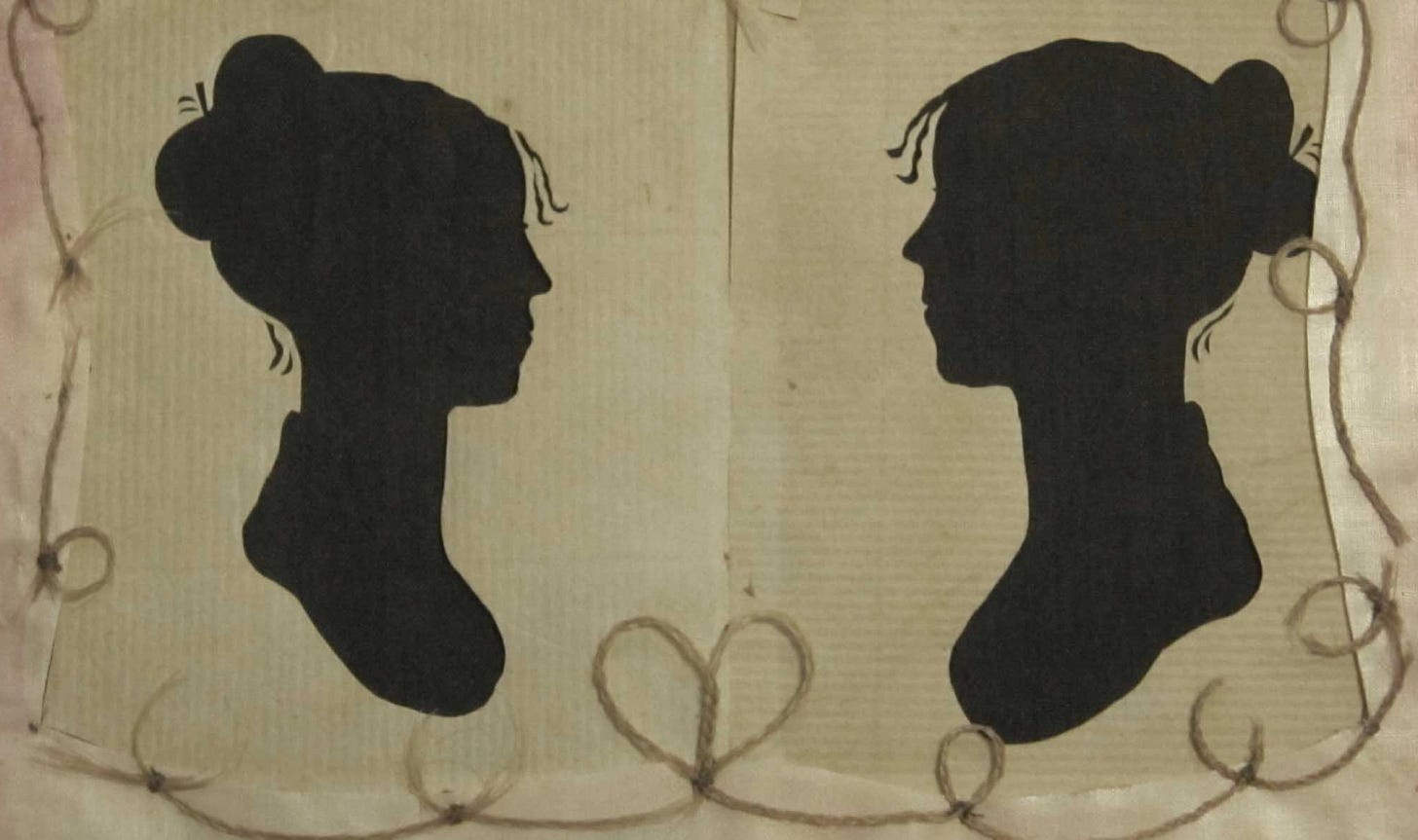

After all, in the real world of 1856, just 150 miles north of Abigail and Tallie’s Catskill farmland, Sylvia Drake was living out her final years in Weybridge, Vermont, having said goodbye in 1851 to her wife of 44 years, Charity Bryant. When Sylvia passed away in 1868, the citizens of Weybridge, who had long understood the nature of Charity and Sylvia’s relationship, buried her with Charity under an embossed headstone, a gesture reserved for spouses.

Charity and Sylvia, much like Abigail and Tallie, were women of a farming community. Weybridge in 1807 was a wilderness of northern New England populated by families seeking a fresh start in the wake of the 1790s post-war economic collapse. And where The World to Come imagines such a society as one with harsher, more dogmatic views around same-sex couplings, the reality was quite different. This was a world of pioneers, who prioritized the roles that made a community thrive over the moral transgressions of the individuals who occupied them. As pillars of Weybridge town life, Charity and Sylvia’s love could more or less comfortably exist as an open secret. Rachel Hope Cleves, author of Charity & Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America, writes,

Queer history has often focused on the modern city as the most potent site of gay liberation, since its anonymity and living arrangements for single people permitted same-sex-desiring men and women to form innovative communities. More recognition needs to be given to the distinctive opportunities that rural towns allowed for the expression of same-sex sexuality. For early American women in particular, the rural landscape rather than the city served as a critical milieu for establishing same-sex unions. Women of Charity and Sylvia’s generation spoke far more often of their desire to retire together to a little cottage in the countryside, than of their urge to move together to a city.

In the wilderness of undiscovered country, women like Charity and Sylvia found a solitude and sense of purpose that allowed their relationship to grow and find credibility. Fears of dogmatic retribution and denial from heaven were never far from their minds, but the threat they felt most keenly came directly from God, not a neighbor. This is much more akin to the life Abigail and Tallie might have found for themselves in the real world of their setting, and by projecting 21st Century sensibilities of queerness and homophobia onto their love story, The World to Come offers an unfortunately limited and often inaccurate picture of what the danger facing these women really was and where it originated.

At the third-act turn of the story, Abigail begins to worry that she hasn’t seen or heard from Tallie in weeks. She fears that something terrible has happened, remembering anecdotal stories from Tallie of her husband Finney’s casual cruelty. When Abigail braves the walk to Tallie’s farm, she finds it abandoned with evidence of violence and her fears worsen. Months pass, at last Abigail receives a letter from Tallie. It is full of affection and longing, the words of a frightened, isolated woman reaching out to her most precious companion.

In Shepard’s text, this letter is where Tallie’s story ends. Abigail and her husband Dyer resolve to travel north to find Tallie and Finney. When they arrive, Finney remarks on Tallie’s death like reporting the weather, though relishing how visibly upset it makes Abigail. Abigail refuses to leave until Finney tells her where Tallie is buried, and in the nearby woods at an unmarked grave Abigail says goodbye to her love.

In the film, however, we see more of Tallie’s misery in an even deeper, wilder northern wilderness, trapped in a cabin with her abuser. When she writes her final letter to Abigail, Abigail writes back, echoing Tallie’s desirous longing and making clear her own. The letter is emotional, intimate, but decidedly not explicit. But Finney gets a hold of it and reads it aloud to Tallie with the bitterness of a man betrayed. In his reading of Abigail’s letter, he acknowledges his wife’s sexuality. He acknowledges his jealousy that his wife is having sex with a woman, and his pain is felt as a man emasculated by adultery, and thus he resolves to kill her for it.

The depiction of romantic and sexual jealousy from husbands toward their wives in this story, particularly Finney’s, is confounding. Not only is it frustrating for the film to spend an inordinate amount of time prioritizing the relationship between Abigail and Dyer over that between our leading lovers, but it creates a kind of sexually competitive spirit that is far, far too modern for its setting.

Before Charity found a wife in Sylvia and the pair were able to live as openly as a gay couple could at that time, more openly than some are even now, she engaged in the common 19th Century practice of “romantic friendship.” These relationships were marked by their intimacy, and were viewed as a vital and beautiful part of a young person’s life. A meaningful connection to a friend of the same sex meant the assurance of a confidant who could set you on the path toward a happy, advantageous marriage. Within these connections, a certain level of physical intimacy was expected. Charity, and indeed many lesbians and queer men and women of the time, found romantic friendships to be the perfect context in which to engage in meaningful sexual relationships. The letters written between Charity and her “friends” during her early 20s were precisely the sort of letters written between Tallie and Abigail.

Romantic friendships were extremely common and rarely garnered suspicion, so long as the friends eventually found suitable spouses. Cleves writes of this, “Concerns arose when friendships seemed to interfere with marital futures.” And indeed, when Charity inevitably ended up in hot water with her lovers (and their parents) it was because she was keeping them from finding husbands. Considering Abigail and Tallie are both married when their connection begins, it makes even less sense that their dynamic is so immediately met with scrutiny, suspicion, and jealousy from Dyer and Finney. An intimate friendship between two married women with no human contact besides their husbands would not only not be a source of concern, but might even be encouraged for the good of community-building.

When it comes to these husbands, Dyer’s feelings about his wife are more complex than Finney’s. He and Abigail have been the company to each other’s misery as they grieve the recent loss of a young daughter. Dyer feels abandoned when Abigail starts to smile again, and insecure when he learns the source of that smile is not him. But the film confuses this as him perceiving Tallie as a legitimate rival, which she simply would never be. It would be more accurate to paint Dyer’s annoyance at the women’s close friendship as that of an employer who keeps coming home to find his employee on a break, having done none of her work. For all the genuine love we’re meant to believe this husband has for his wife, that is the reality of the love-labor balance in such a marriage.

Indeed, this is Finney’s chief complaint about Tallie. Even outside of her friendship with Abigail, she refuses to perform any labor on their farm. Like Tallie, Charity was viewed as an oddity and problem to her family not because she spent too much time with other women, but because she refused to do the work society had deemed it her responsibility to do. She was a failure, a freak, of a woman because she did not labor as a woman ought.

Therefore, harrowing and troubling as it is, the decision to motivate Finney’s murder of Tallie as a crime of jealousy is frankly giving too much credit to how this man would have perceived his wife and her lover (whom it never would have occurred to him Abigail was). In the short story, Shepard makes this much clearer than in the film: Finney kills Tallie because he can, because it feels like the logical and necessary thing to do. It is as simple a choice to him as when he slaughters his pigs. Tallie is another animal on his farm who refuses to fulfill her duties to him, and is therefore a waste of resources.

And here is the critical clarification: when we talk about how a couple like Charity and Sylvia were able to live together as spouses, or how in nearby Amherst, Emily Dickinson was carrying on a decades-long love affair with her sister-in-law Sue Gilbert, or how in England, Anne Lister was adventuring Europe with her wife Ann Walker, we are not imagining a world where queer women were celebrated and liberated. We are talking about a world in which the concept of sex between women was barely believed possible, let alone legitimate. In this world, women occupied a place in society such that the bonds between them warranted little attention, let alone active and vengeful jealousy. The invisibility and impossibility of romantic or sexual connections between women offered a kind of backwards freedom, allowing those connections to thrive. We see this even now, when tabloids publish their infamous “gal pal” stories about obviously queer celebrities, refusing to see what is plainly true.

This is the messy wheel of progress when it comes to queer history and how we portray it in our stories. When we look backwards, we imagine only suffering, its horror calibrated to the present moment we’re in as an audience. In one of the rare scenes of joy between Abigail and Tallie, Abigail speaks of her feelings as a pleasant prison, resigning herself to the notion that their love renders them caged, though happily so. Tallie is surprised and confused by the comparison. She does not feel imprisoned with Abigail, she senses no cage around her feelings. This cage Abigail speaks of is a 21st Century invention, created by a society that cannot feel the satisfaction of its own progress without projecting prisons into the past. Abigail dreams of a world to come, a world beyond this cage. Tallie sees the world that they have. She understands that the world to come is one that they themselves are responsible for making, just as Charity and Sylvia did, just as so many - many more than the history pages will ever tell us - have always done.